NeurIPS - Ariel Data Challenge 2025 Review

Preface

I participated in the NeurIPS - Ariel Data Challenge 2025[1], held from June 27, 2025 to September 25, 2025, and achieved 7th place out of 1,038 participants and 860 teams, earning my first gold medal. In the middle of the competition, I teamed up with takaito, who is also a Kaggler. It would have been extremely difficult to win a gold medal solo, so I am very grateful to takaito for the discussions and efforts we shared during the competition. I had already followed takaito during the IceCube competition; he was one of the first Kagglers I remembered, so I was very pleased to have the opportunity to team up this time.

Our team’s solution has been published on Kaggle. For detailed methods and technical information, please refer to: 7th Place Solution.

This article will not focus on technical details, but rather on my reflections and experiences from the competition.

Before participating in ADC2025, I was actually competing in the NeurIPS - Open Polymer Prediction 2025. However, due to severe data leakage, I decided to withdraw from that competition. In retrospect, this was the correct decision, as Open Polymer Prediction has completely lost its scientific value.

Overview

To date, more than 5,600 exoplanets have been discovered. Detecting these planets is only the first step; understanding their nature, especially their atmospheric composition, is key to revealing the possibility of “another Earth.” In 2029, the European Space Agency’s Ariel mission will conduct the first comprehensive study of 1,000 exoplanets in our local region of the Milky Way. This competition is set against the backdrop of ESA’s Ariel space telescope, simulating the spectroscopic observation tasks during exoplanet transits.

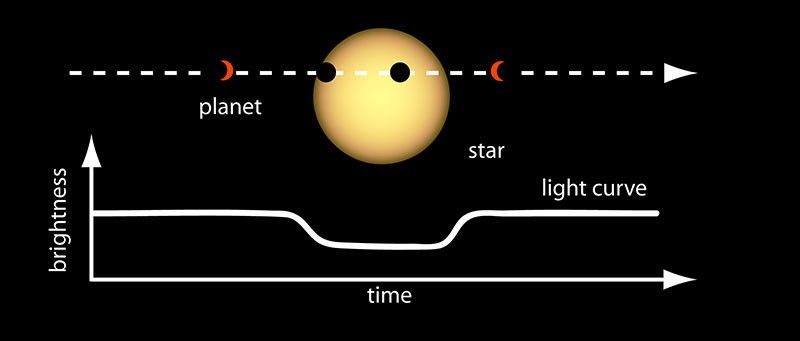

A “transit” occurs when an exoplanet passes in front of its host star from our line of sight, as illustrated in the figure below.

Figure 1 Transit Diagram[2]

During this event, the star’s brightness experiences a slight but measurable dip. Part of the starlight is blocked by the planet itself, while a smaller portion passes through the planet’s thin atmosphere, where it is absorbed and scattered by atmospheric molecules (such as H₂O, CO₂, CH₄, etc.), resulting in a greater decrease in brightness at certain wavelengths λ.

This wavelength-dependent transit depth $\delta(\lambda)$ forms what is known as the “transmission spectrum,” which carries information about the chemical composition of the planet’s atmosphere.

The transit depth can also be estimated using $\left( \frac{R_p(\lambda)}{R_s} \right)^2$, and thus can be interpreted as the ratio of the planet’s radius to the star’s radius at different wavelengths.

Therefore, we need to predict the transit depth $\delta(\lambda)$ (wl_pred) and its corresponding uncertainty sigma $\sigma(\lambda)$ (sigma_pred) at 283 wavelengths, meaning each sample has 566 targets (283 × 2), representing the physical signal strength and confidence at each wavelength. The competition uses the Gaussian Log-likelihood (GLL) function, which is an extremely sensitive metric—small changes in sigma can lead to significant differences in score. This places very high demands on the model’s ability to express confidence in its outputs.

Early Stage

ADC2025 is an enhanced version of ADC2024. Although some Kagglers suggested to “forget everything you know about ADC2024,” I still carefully reviewed and absorbed the lessons from 2024. In the early stage, I mainly focused on integrating and restructuring the top solutions from ADC2024, and quickly reached the gold tier.

Around July 19, the dataset was updated. The original data did not account for the orbital period of the planets, resulting in unreasonable transit times. This update further increased the difficulty, introducing anomalous samples with excessively long transit durations, making it impossible to observe any out-of-transit segments. After extensive bug fixes, I was still able to maintain a position in the gold tier.

Thanks to this round of bug fixing, I gained a much deeper understanding of the data. The idea of using low-order polynomials in my solution also originated from this stage. I believe this was crucial for improving the stability of our method on the private test set.

Middle Stage

takaito quickly reached the gold tier in the middle stage. Although my initial plan was to merge teams after reaching a score of 0.5 solo, I gradually felt increasing pressure from competitors such as Ethylene and JFPuget+Dieter. Additionally, takaito had achieved 15th place in 2024 with a neural network-based approach. I believed his experience and different methodology would provide significant exploration potential, so I decided to contact him first. When our highest score reached 0.596, we decided to merge our teams.

takaito built and optimized his solution based on last year’s deep learning approach. While I focused on constructing a detailed physical model and a stable baseline for wl_pred, he used a much simpler physical baseline and concentrated on optimizing the neural network model. This was highly complementary to my deep exploration, and after combining our methods, our score improved significantly and quickly surpassed 0.5.

My original approach mainly focused on improving forward modeling and simple post-processing (such as PLS). With takaito’s participation, I was able to abandon the previously coarse post-processing and instead utilize the neural network component that I had not successfully applied before. This allowed us to make more effective use of the features and information derived from my physical modeling, for which I am very grateful. The sigma correction step was also significantly improved at this stage, based on the method introduced by takaito.

Final Stage

The pressure increased steadily in the final stage, and we were unable to return to the prize-winning positions. Although I tried to find a breakthrough by searching for “magic” in data preprocessing and other areas, these attempts ultimately failed. I referred to the “magic” from 2024 and experimented with various tweaks to the preprocessing, but none of them had any impact on the final results, which was quite frustrating. Both takaito and I speculated that at least two teams might suddenly jump to the gold tier in the final phase, so we shifted to a strategy of steadily improving our score, making small adjustments to each model. Considering the time constraints, I even used two A100 GPUs at this stage to maximize the number of parallel experiments.

In the last two days, I barely slept, staying up until around 9 a.m. Japan time to make full use of all remaining submissions.

On the final night, we were still adjusting the last pipeline. Our implementation continued to have various minor bugs, so we did not finish all submissions until 26:00 Japan time. To ensure the final submission could be completed on time, takaito had to compromise by reducing the computational load of Pseudo Labeling. I sincerely feel sorry for my mistakes.

In the end, we barely managed to submit on time, but our highest-scoring submission was unfortunately eight minutes late.

Conclusion

In the end, I anxiously waited until the morning, and after the shake, we achieved 7th place. I believe my biggest mistake was using the wrong neural network output when training the sigma correction model on the final night, which forced me to spend an extra 40 minutes retraining. Without these errors, we might have been able to select the best pipeline. I deeply realized that “the more anxious you are, the more likely you are to make mistakes.”

However, I think the timing of our team merger was perfect, allowing us to fully utilize our time to integrate our methods and conduct thorough exploration and discussion. Our approaches complemented each other very well, covering each other’s weaknesses. From my perspective, our final method was somewhat redundant and lacked elegance, but overall, it was highly effective.

As takaito’s blog describes, after completing the final submission, we found ourselves with nothing to do, so we immediately started writing the solution. As a result, we became the first team to publish a solution the next day, which was a very interesting experience.

Looking back, I maintained a gold-tier position for almost the entire competition, which was honestly quite challenging.

In terms of results, I am very happy to have won my first gold medal. However, this is not something I could have achieved alone, and in the future, I hope to aim for a solo gold medal and Grandmaster.

If ADC2026 is held, I will definitely participate.

Thank you to everyone for your hard work.

Reference

[1] Kai Hou Yip, Lorenzo V. Mugnai, Rebecca L. Coates, Andrea Bocchieri, Orphée Faucoz, Arun Nambiyath Govindan, Giuseppe Morello, Andreas Papageorgiou, Angèle Syty, Tara Tahseen, Sohier Dane, Maggie Demkin, Jean-Philippe Beaulieu, Sudeshna Boro Saikia, Giovanni Bruno, Quentin Changeat, Camilla Danielski, Pascale Danto, Jack Davey, Pierre Drossart, Paul Eccleston, Billy Edwards, Clare Jenner, Ryan King, Theresa Lueftinger, Michiel Min, Nikolaos Nikolaou, Leonardo Pagliaro, Enzo Pascale, Emilie Panek, Alice Radcliffe, Luís F. Simões, Patricio Cubillos Vallejos, Tiziano Zingales, Giovanna Tinetti, Ingo P. Waldmann. NeurIPS - Ariel Data Challenge 2025. https://kaggle.com/competitions/ariel-data-challenge-2025, Unpublished. Kaggle. . NeurIPS - Ariel Data Challenge 2025. https://kaggle.com/competitions/ariel-data-challenge-2025, 2025. Kaggle.

[2] Light Curve of a Planet Transiting Its Star https://science.nasa.gov/resource/light-curve-of-a-planet-transiting-its-star/